Dimensions: 210 x 210 mm

Pages: 32

You can view the entire catalogue online here for free by clicking on view sample pages, but we would be delighted if you would like to purchase a hardcopy.

Introductory Essay

“May you live in interesting times…” and from the perspective of this United Kingdom, on the verge of cataclysm or liberation depending on your viewpoint, rarely does this well-worn invitation ring so true as it does right now. So, why are we taking a step back to the late 18th Century with this exhibition of the work of James Gillray in the gallery this month?

Gillray is arguably the father of the modern political cartoon and we can certainly indulge a degree of patriotic pride in the distinctly British contribution to this artform. Gillray, alongside other luminaries such as Hogarth, Rowlandson and Cruikshank established a tradition of graphic satire in the 18th Century that has been sustained in rude health ever since by the likes of Tenniel, Low, Scarfe, Brooks and Bell. It is also a tradition that is inseparable from the history of printmaking itself. The widespread distribution of images, words and ideas made possible by the development of the cast iron etching press demanded a new visual language and Gillray marshalled the full range of intaglio techniques, from stipple engraving and drypoint, to roulette roller and aquatint to codify this new artform. His skills found ready employment by the industry of printers and publishers that flourished in Georgian London to cater for the expanding appetite for graphic satire.

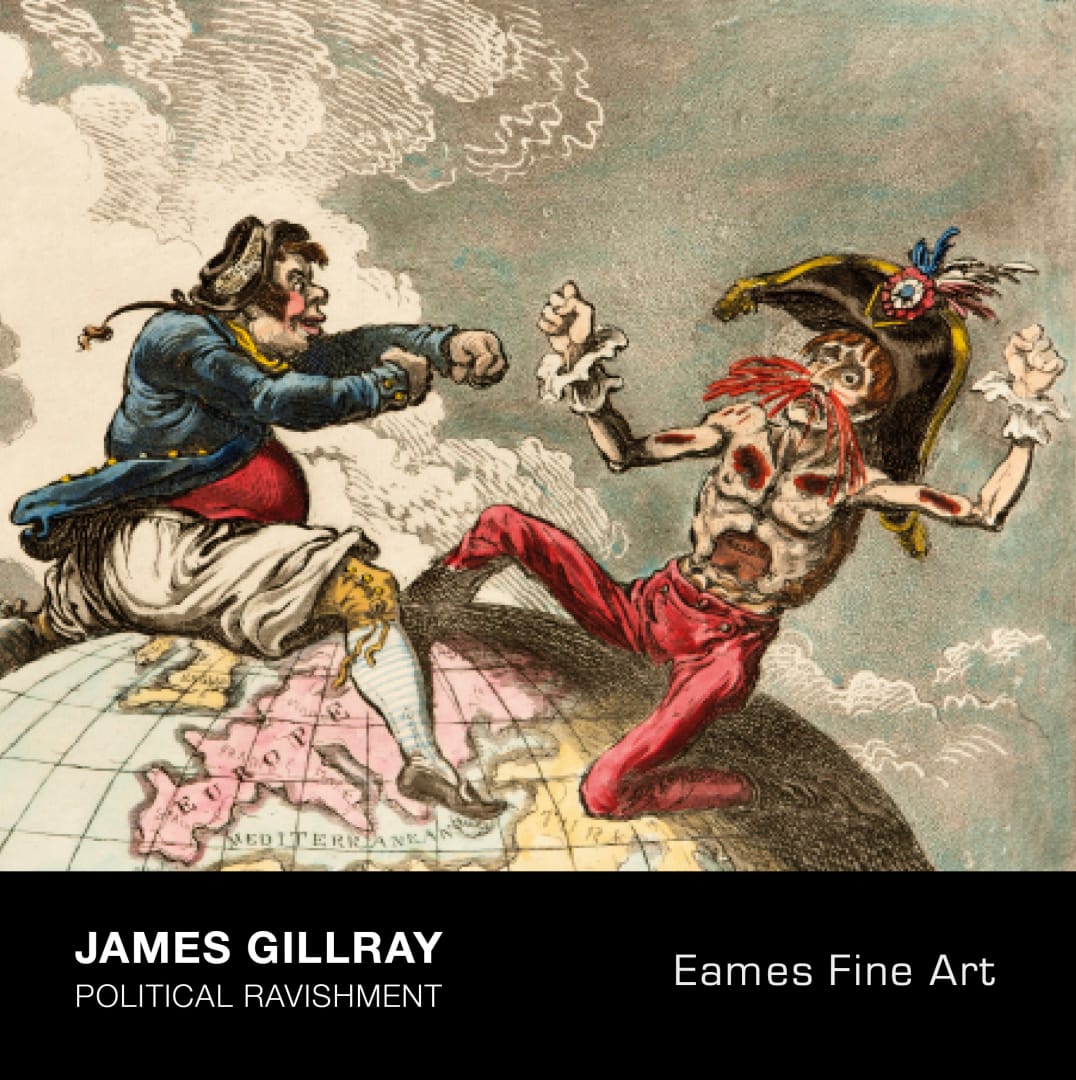

Perhaps Gillray’s defining achievement however is in the way he applied the tenets of comic caricature, imported from continental Europe, to the British tradition of satirical engraving. This transformed an elaborate vocabulary rooted in emblematic, allegorical types that required sometimes extensive explanation, into a much simpler and vital form of communication. Gillray placed his caricatures into widely understood metaphorical contexts sourced from the Bible, ancient myths, the Classics, Shakespeare and folk proverbs to translate complex political situations into a single image. The effect was savage.

Gillray’s example was readily seized upon by his contemporaries and in another example of a European cross-pollination of ideas, the ‘First Master of the Modern Age’, Francisco de Goya in Spain, made extensive use of his prints as source material for Los Caprichos - his era-defining suite of etchings that helped to usher a new, raw, modern visual language into Western Art. While Goya’s debt to Gillray might attest to his wider cultural significance, a more contemporary relevance is acknowledged by a present-day practitioner of the satirists’ art. Martin Rowson, political cartoonist for the Guardian newspaper writing in 2015 on the 200th anniversary of Gillray’s death, suggested that his example shows us that:

“Satire is a survival mechanism to stop us going mad at the horror and injustice of it all by inducing us to laugh instead of weep”

Accordingly, we hope that this show can be of some use to you this March.

Vincent Eames, March 2019