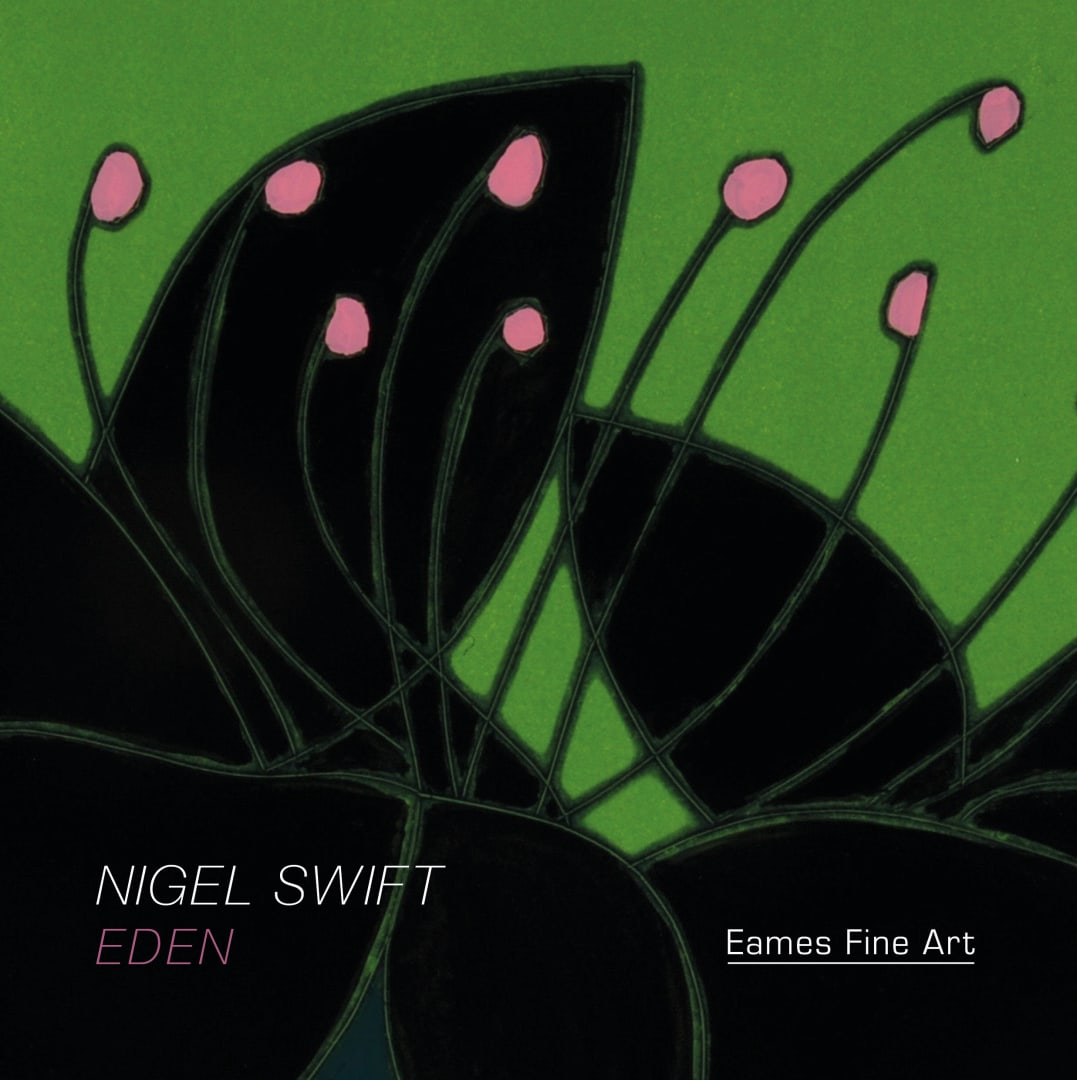

Dimensions: 210 x 210 mm

Pages: 32

You can view the entire catalogue online here for free by clicking on view sample pages, but we would be delighted if you would like to purchase a hardcopy.

Introductory Essay

To some, Nigel Swift’s newest exhibition, Eden, may seem like a departure for the artist. Nigel’s last solo show at Eames Fine Art focused on ethereal, mysterious, mythical landscapes, while this collection features flowers, insects, plants and bouquets in vases. However, when one steps back to consider the narrative underpinnings of this artist’s most recent show Genesis, as well as some of his earlier work, Nigel’s trajectory of artistic thought and inspiration is clear. There are connections – both obvious and implicit – that tie this exhibition to Nigel’s previous collections.

With Genesis, Nigel took us back to the beginning of time, to the creation of the universe, before humans. In terms of living creatures, his vast imagined landscapes only included birds flying above calm seas or Van Gogh-esque trees against marigold skies. With Eden, Nigel remains visually in this era long before the Anthropocene; but this is his chance to populate the dream world that he created in his last show. These works home in on the small living things – the plants, flowers and some animals – that inhabit the deserts, coasts and mountains that he depicted in his Genesis landscapes. As he said in his description of his most recent show, returning to this pre-human era is “amazingly liberating”, as this is a world that he can create himself, with no rules of set visual tropes or expectations.

In addition to the images of individual flowers and plants, Nigel has also produced jewel-like paintings of colourful, bounteous bouquets of flowers in vases. These, like his Genesis landscapes or his other Eden flowers, are imagined objects. These fictitious compositions can be compared to the work of Dutch still-life painters such as Ambrosius Bosschaert and Rachel Ruysch. Both painted carefully observed and detailed images of flowers in vases but overpopulated the containers with more plants than could realistically fit, imagining a more voluminous, voluptuous bouquet than what could appear in reality. Several works from 2019 demonstrate that this subject, which sits alongside the more obviously ‘Edenic’ images, is something that Nigel has been ruminating on for quite some time. These older flower vase images, when viewed alongside more recent examples, convey some of the main messages of this exhibition. For example, Untitled 321, a monoprint showing spiky flowers reaching out of a vase dwarfed by leaves and petals, alludes to some of the more mysterious themes of this Eden exhibition. In this piece, the beauty that is expected in a vase of cut flowers is shrouded in shadows. Five ‘hands’ seem to reach out from the centre, giving the bouquet an eerie, animated agency. We get a similar sense with Untitled 104 (Sunflower). This flower, anthropomorphised, turns its ‘head’ directly towards the viewer. Its chunky green and yellow leaves and petals – which in the other Sunflower works politely flop away from the audience, not towards them – seem to reach out to the front of the picture plane like hands. Nigel has transitioned the grasping, yearning energy of the 2019 monochrome bouquet into the more sentient presence of this sunflower.

Looking even further back in Nigel’s exhibition history, we could think about how his joint show with Anita Klein in 2016, inspired by their time in Australia, is mirrored in the themes and works of Eden. Australia is known for its sublime, breath-taking landscapes and vistas. But in Australia there is also a threatening, dangerous side to the beauty of the flora and fauna. It was during his time in Australia and during the creation of the artworks featured in that joint exhibition that Nigel began to consider the paradoxical nature of nature: how can something so gorgeous be so treacherous? A first glance of the works featured in Eden offers an impression of springlike colour and overt optimism. However, there is in this show a slight unease, a sense that these images are too good to be true, too beautiful to be completely safe – like the dangerous wildlife of Australia or the menacing aforementioned sunflowers and bouquets. There is wrapped up in these too-beautiful flowers the cultural trope of the siren, or the femme fatale: these images draw viewers in, seduce people – their enticing beauty only turning dangerous once we get too close. They are the incarnation of Charles Baudelaire’s title for his 1857 collection of poetry: Les Fleurs du Mal, or, Flowers of Evil. This phrase is one that preoccupied Nigel whilst making the pieces for Eden.

In addition to this coexistence of beauty and threat, there is also a trickle of poison or decay running through these images of flowers. The bright pinks in Untitled 227 stand out against the blue-black of its petals like the warning pattern of a black widow spider. The title of Untitled 122 (Fading Flower) is a direct allusion to the fact that no matter how beautiful, and whether innocent or toxic, all flowers are fragile and short-lived beings. Again, Nigel is working within a tradition of artists like Ruysch, who would include insects in her paintings of flowers as a memento mori: a reminder that even these beautiful things will perish, or be eaten. Nigel’s Fading Flower composition makes explosive the falling motion of the passing of a flower from bloom to decay. The weighty petals of various shapes and sizes float away from the centre of the flower, its stamen and pistil. Nigel has captured an imagined moment of this flower dissolving into death, before it returns to the dirt from whence it came, while the colour and shape still retain much of its beauty. Of course, the garden from which Nigel takes the name of this exhibition was itself a place with an expiry date and also a place of peril, temptation and (morally) poisonous vegetation. All of these civilisations-old ideas are wrapped up into this innocent-seeming springtime exhibition of bright colour.

Christine Slobogin, March 2021