Like many of the other artists represented by Eames Fine Art, Míla Fürstová has been busy on new projects during the last year's lockdowns. From her press in her home in Cheltenham, Míla has been making new prints, exploring fresh ideas while also building on some of the fantastical and ethereal subjects and styles that her collectors know and love.

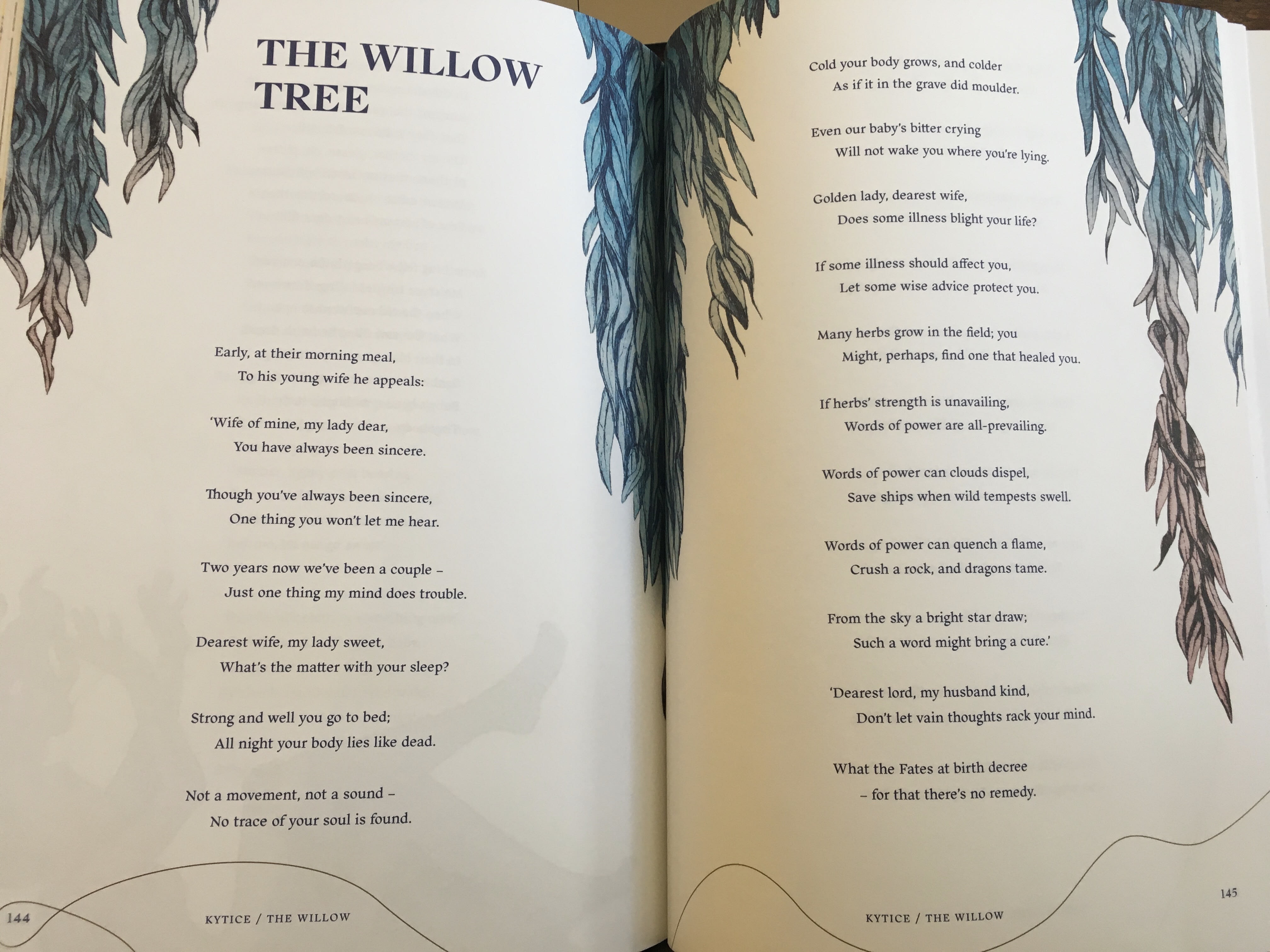

One of the primary projects that Míla has been working on is the illustration of some of the most beloved pieces of Czech poetry: the collection Kytice by Karel Jaromír Erben, originally published in 1853. Erben is one of the greatest Czech poets of all time, and this new English language publication of Kytice (which translates to ‘A Bouquet of Folk Legends’), published by Jantar in London, marks the 150th anniversary of the poet’s death. It is a huge honour for Míla to be given the opportunity to illustrate these canonical poems, which every Czech child reads. This new publication has been a roaring success in her home country of the Czech Republic (you can see a twenty-minute feature on Czech national television, in Czech, here and a radio feature, in English, here), and the project continues to garner interest in the UK. This translation is a chance for English speakers to dive into the dark, moralising, fascinating world of Erben’s literature, with Míla’s gorgeous artwork visualising the tales. For Míla, Erben’s stories were a form of escapism during the lockdowns. Through his poems she could travel to his magical worlds of danger and drama, all while being confined to her home.

We are pleased to offer these works by Míla, made for the publication but available as original prints from an edition of 50, to Eames Fine Art clients for 10% off. Please click here to access the viewing room of Kytice artworks.

Not only are we selling these gorgeous Kytice illustration pieces at a discount, but we’re also extending this to any of the Míla Fürstová artworks listed on the Eames Fine Art website. You can access her page here. We also have some fantastic films featuring Míla and some of her past projects available to view on our website here.

Please contact the Studio on 0207 407 6561, or [email protected], with any enquiries about framing or about purchasing the works.

Reading through this esteemed Czech poet’s work, Míla’s emotion- and narrative-laden printmaking style seems like it must have been an obvious choice for illustrating the verse. Much like the Victorian fairy tales that are famous in Britain (such as those by the Brothers Grimm), these stories ruminate on the meaning of ideas as broad and as universal as death, childhood, greed, and good and evil. These themes, while written in the language of an age long ago, are still applicable to the lives of audiences today.

In addition to the standalone images below, details of Míla's etchings are interlaced with the text, providing small references to the environment in which the poems takes place.

Míla states about Erben’s poetry: “The environment is almost a protagonist”. And her work, as it always does, brings human characters into dialogue with the forests, lakes, and cities that envelop them. Míla’s images draw us into the wildernesses, homes, and cemeteries mentioned throughout Erben's Kytice collection. She breathes humanity and whimsy into what could have remained just staid backdrops for the plot. Instead, natural elements like branches, weather, and hills become part of the action themselves. This practice of Míla’s highlights to us the interactive relationship that all humans have with their natural surroundings.

For those of us who aren’t familiar with Erben’s poetry, I’ve taken the liberty of summarising each of the eight main poems that Míla illustrates, along with a short analysis of how her gorgeous etchings bring out subtleties of each story. Overall, Míla’s artworks highlight the beauty of these poems, and of the human experience, not the gothic gore or horror that also often permeates Erben’s work.

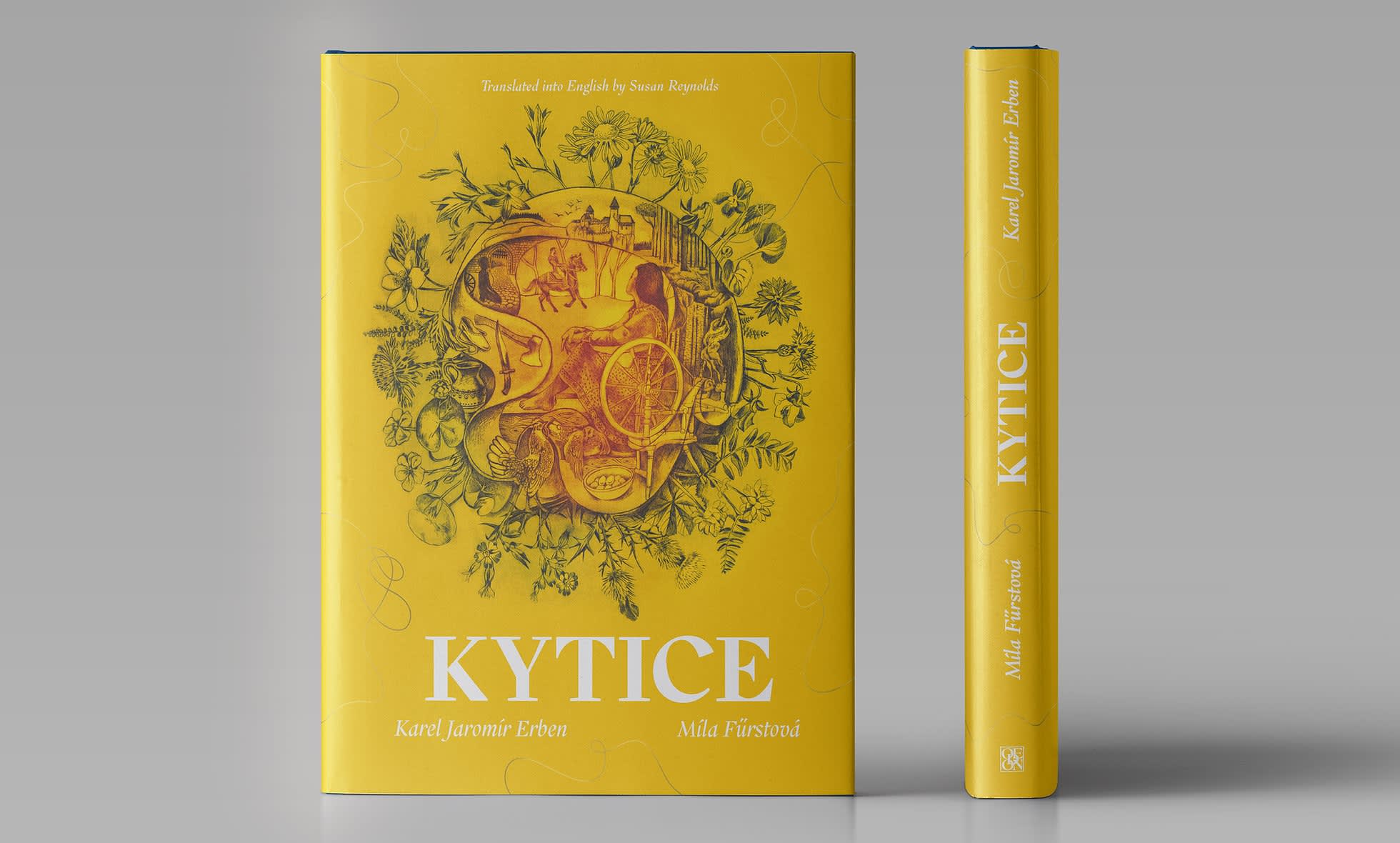

The Treasure (yellow)

This poem tells the story of a mother who on Good Friday, with choirs singing hymns in the background, stumbles into a cave full of gold and silver treasures. As she scoops the pieces up – sure that God means for her to have this fortune – she realises that she cannot carry the treasure and her son. She chooses the gold and silver. After transporting the treasure to her home, it turns to clay, and she realises that she’s left her child in the cave with this “treacherous hoard” (p. 43). When she returns, there is no cave, there is no treasure, and there is no child. It is only in exactly a year’s time that she is able to find the cave again and miraculously retrieve her son.

Míla’s etching of this story centres on the spiritual bond between mother and child, one that is never to be taken for granted, as this story teaches. This pairing of the mother and son is the part of the image that is emblazoned in red. But the darker elements of this etching (the coins falling from the shadowed trees of blue) hint at the frightening, bleaker side of this tale.

The Wedding Shirts (blue)

In this poem, a woman’s sweetheart has been away in “foreign lands” (p. 56) and has yet to return after three years of no news. She prays a blasphemous prayer to a picture of Mary to either bring him back to her or to end her life. He immediately appears and whisks her off on an eerie journey through the night. He promises that he’s taking her to their wedding, but in reality, he takes her to his grave. He is intent on dragging her into the afterlife as a punishment for her blasphemy. A battle with the evil groom ensues, but in the end the maiden succeeds and survives.

Míla deftly delineates between the live woman and the deceased lover here by splitting the colours of her etching between them. The woman is cloaked in a warm reddish hue while the man emerges out of a crepuscular blue, his eye sockets and shadowed cheekbones prominent, evoking skeletal comparisons. His body is aligned with the moon surrounded by clouds, while beneath the young woman’s legs, Míla’s use of colour and space suggests a sunrise over a church – hinting at new life and new beginnings for the maiden who has been spared.

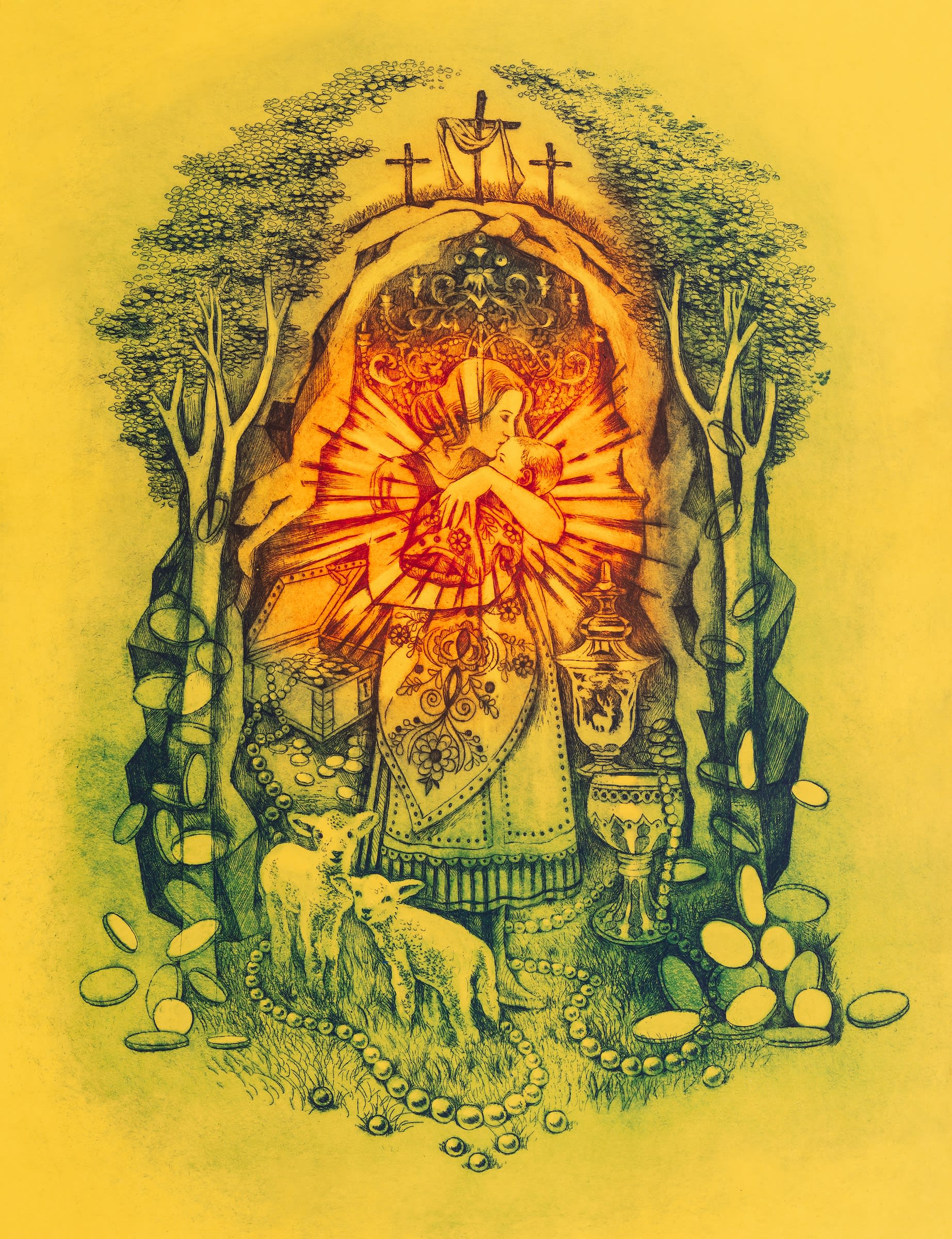

The Noonday Witch (yellow)

This shorter poem is one of the more gothic, horror-infused pieces in Kytice. A mother is chastising her loud child and threatening that the ‘Noonday Witch’ will come to get them if they don’t behave. Little does she expect the witch to truly arrive, and she fearfully holds the child so tight that when the father appears in the doorway moments later, and the witch vanishes, the child has been smothered.

Míla takes on this terrible story with care. There is palpable fear in the image: the mother’s upturned face draws the viewer’s eye to the dark and ominous cloaked figure of the witch. But once again, as in Míla’s etching for The Treasure, the focus is on the bond between mother and child. They are tied together closely while the terrors of time – of noon – hover above the pair in a clock surrounded by swallows.

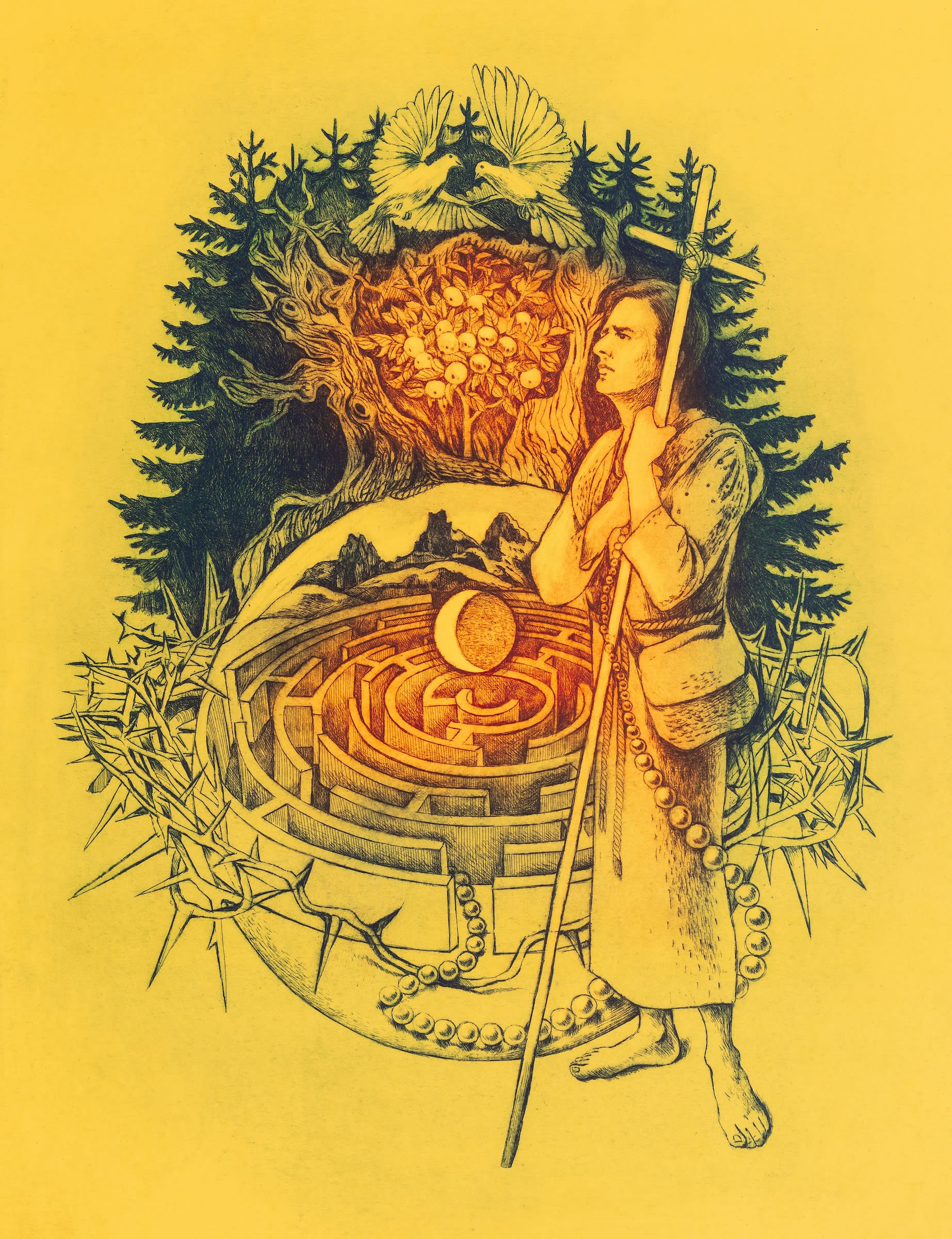

The Golden Spinning-Wheel (yellow)

This poem opens with a king on a “fiery jet-black steed” (p. 77) happening upon a beautiful woman spinning flax; he immediately wants her to be his wife. The girl, named Dora, agrees, but on the way to be wed her evil stepsister and stepmother mutilate her with their knife and axe, substituting the stepsister (who looks very much like Dora) as the bride for the king. A clever, magical, forest-dwelling old man then tricks the evil stepsister by selling her a golden spinning-wheel for the price of the body parts that she took from Dora. When the evil stepsister then attempts to spin, the wheel sings out a song detailing her horrible deeds to the king, exposing her as a fraud. The king then finds his miraculously healed, true fiancée, and they wed: a happy ending.

Míla’s golden etching illustrating this poem serves as the cover image for this publication. Míla does not focus on the gory details of this tale, but rather the narrative shape of the story. The flora included in this image all grow out of the central circular composition. This circle in which Míla has etched the details of The Golden Spinning-Wheel echoes not only the shape of the golden spinning-wheel itself, but also the poetic repetition that appears in this work, and, more symbolically, the way that this story suggests that what goes around comes around. In the end, the good and pure will be rewarded and the evil will be punished.

The Wild Dove (blue)

This is a poem that is much darker than it appears on the surface! It opens on a weeping young widow mourning her deceased husband. Another young man asks her to marry him, and after three days she dries her eyes and agrees to wed. But, as the verse unfolds, it becomes clear that this widow poisoned her first husband. In the end, the guilt becomes too much for the woman, and she feels that the wild dove’s cooing is following her, constantly accusing her of this murder. In the end, this new bride joins her first husband, drowning in her “white dress” (p. 107).

The etching of this tale that is featured in the Kytice book adds to the sense of melancholy felt by the young, weeping widow as described at the beginning of the poem. At first, she seems beautiful and pure, but the reflection in Míla’s etching suggests that the woman is not as she seems: her lovely hair is not apparent in the underwater version of herself, and her delicate features are blurred.

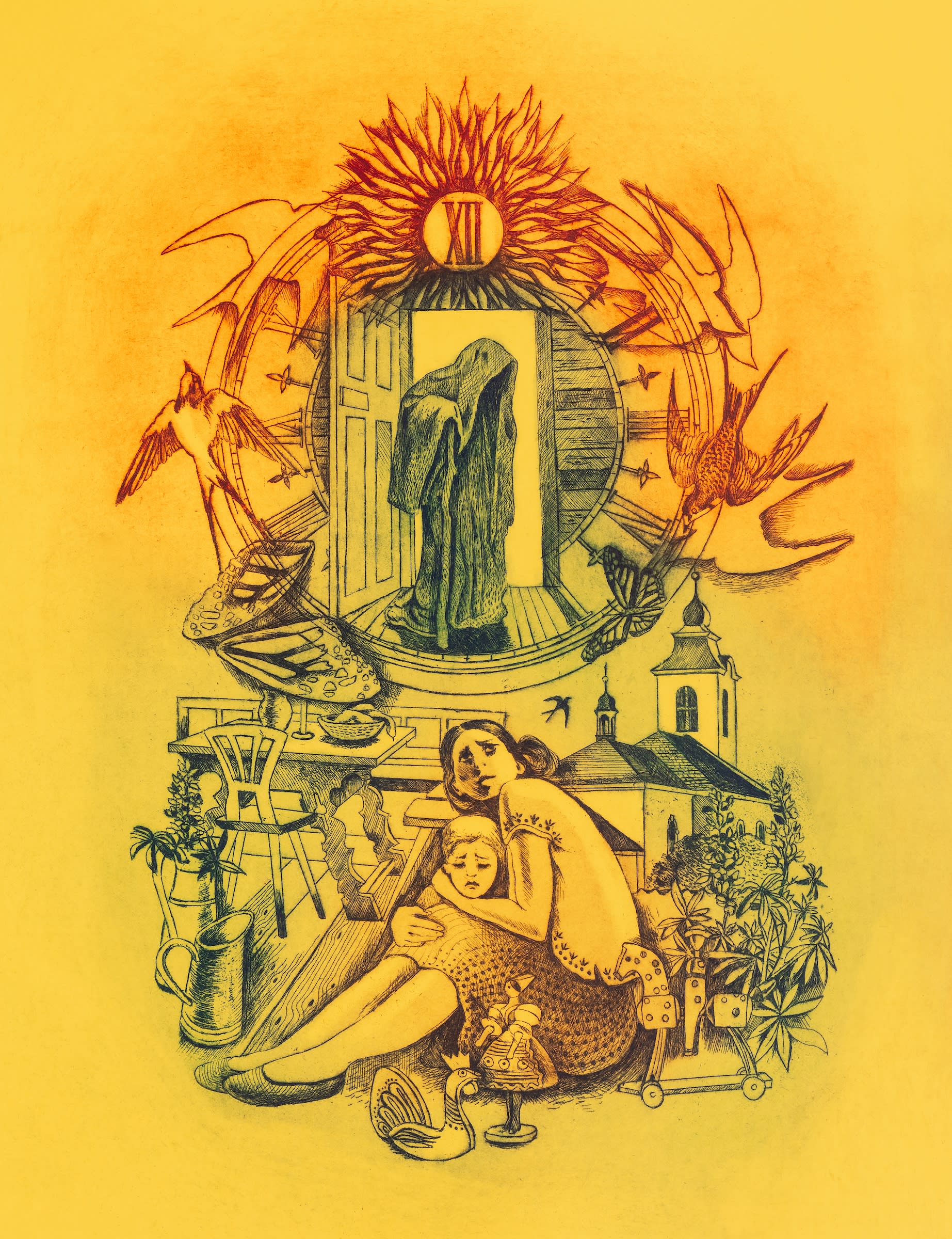

Záhor’s Bed (yellow)

A pilgrim meets a murderous forest man on his way to visit hell; the man, named Záhor, agrees to let him pass if this young pilgrim reports back on what Satan’s kingdom is like. The pilgrim observes many tortures, but the worst of all was called “Záhor’s bed” (p.121) – meant for the forest man himself. After the pilgrim’s report from hell, Záhor repents for his evil ways, asking what he can do to evade Satan’s grasp and his personalised torture. The pilgrim urges him to pray, forgoing food and water, and he plants an apple tree near where Záhor kneels. The forest man’s penitence causes the tree to grow golden, godly apples, and at the end of the poem the two are reunited and turn into “doves of purest white” (p. 129).

The doves that emerge at the end of this poem form the pinnacle of Míla’s etching. They are the symbol of hope and redemption that is arguably most important – and most uplifting – in this story. Míla includes in her composition all that is good about this poem – the doves, the pilgrim, and the golden apple tree. She also encircles the maze of hell with a crown of thorns, emphasising the religious element of this tale.

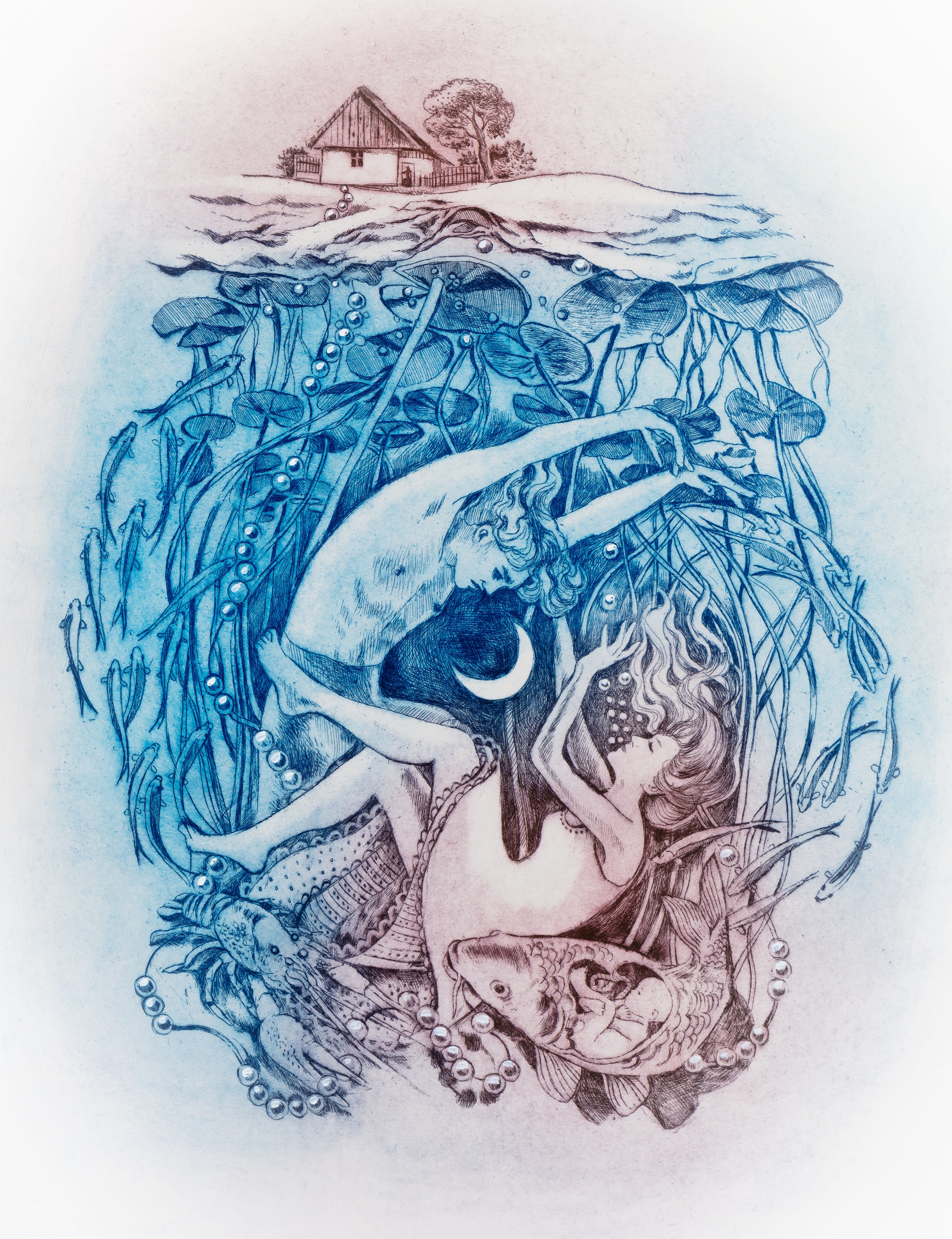

The Water-Goblin (Blue)

A water goblin captures a girl who went to wash her clothes by the lake. She marries him – with crayfish as groomsmen and fish as bridesmaids – and bears him a son; but she is still a captive. After much begging, the goblin allows his wife to visit her mother one last time to say goodbye. She ends up staying with her mother and the goblin punishes her by murdering their baby.

Míla’s etching here has a more romantic tone than the poem as a whole, although there is still the sense that the woman is being smothered by the water and the lilypads, and that the goblin is threatening her with his overbearing posture. Míla deftly uses colour here, signalling what is of the earth (in the warm brown-red tone) and of the lake (in the blue). The woman stands out from her watery surroundings because she does not belong there.

The Daughter’s Curse (yellow)

In this short poem, a girl kills an innocent dove and immediately feels remorse. It then becomes clear to the reader that this ‘dove’ is a metaphor for her own child. In the end, she blesses the lover who fathered the child but curses her mother for giving her a “wilful heart” (p. 159) – in other words, she blames her own mother for her choices and curses her for bad parenting.

The ominousness in Míla’s etching here chiefly lies in the small but prominent detail of the hangman’s noose behind the figure in the foreground. Death is a protagonist in this poem as equally as the daughter is. The dove, in its many iterations, is also a primary protagonist in Míla’s etching. The dead dove sits at the girl’s feet, while the dove representing the holy spirit is emblazoned above the door frame and above the crying daughter. The images that Míla places within the dove’s falling feathers also allude to scenes beyond what is written in the poem, rounding out the reader’s imaginative understanding of the plot. In Míla’s etching, the love between the girl and the boy who is briefly mentioned is given a weightier presence. As in Míla’s etching for The Water-Goblin, the romance of the tale is emphasised.