Continuing our series exploring some of the exciting new projects being taken on by Eames Fine Art artists we're focusing on two pieces of news from our favourite sculptor-draughtsman-printmaker: Malcolm Franklin. First of all, Malcolm has been chosen to exhibit one of his works in the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize; the selection committee included Ian McKeever RA and Frances Morris, director of the Tate. His piece is part of the 'Working Drawings' component of the exhibition, and it is a drawing tied to his other new project from the last year: Ancore. This latter project exhibits Malcolm's talent in many mediums, as Ancore is not just a sculpture, or a collection of sculptures, but it is a site-specific, immersive installation. Below, you'll find a beautiful film about the process and the final product: an engaging, multi-sculpture, mixed media installation in an abandoned theatre in Italy. The rest of this blog post is structured as a Q&A between Malcolm Franklin and myself.

View Malcolm Franklin's available works on his Artist Page here.

CS: How did the Ancore project relate to your entry into the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize?

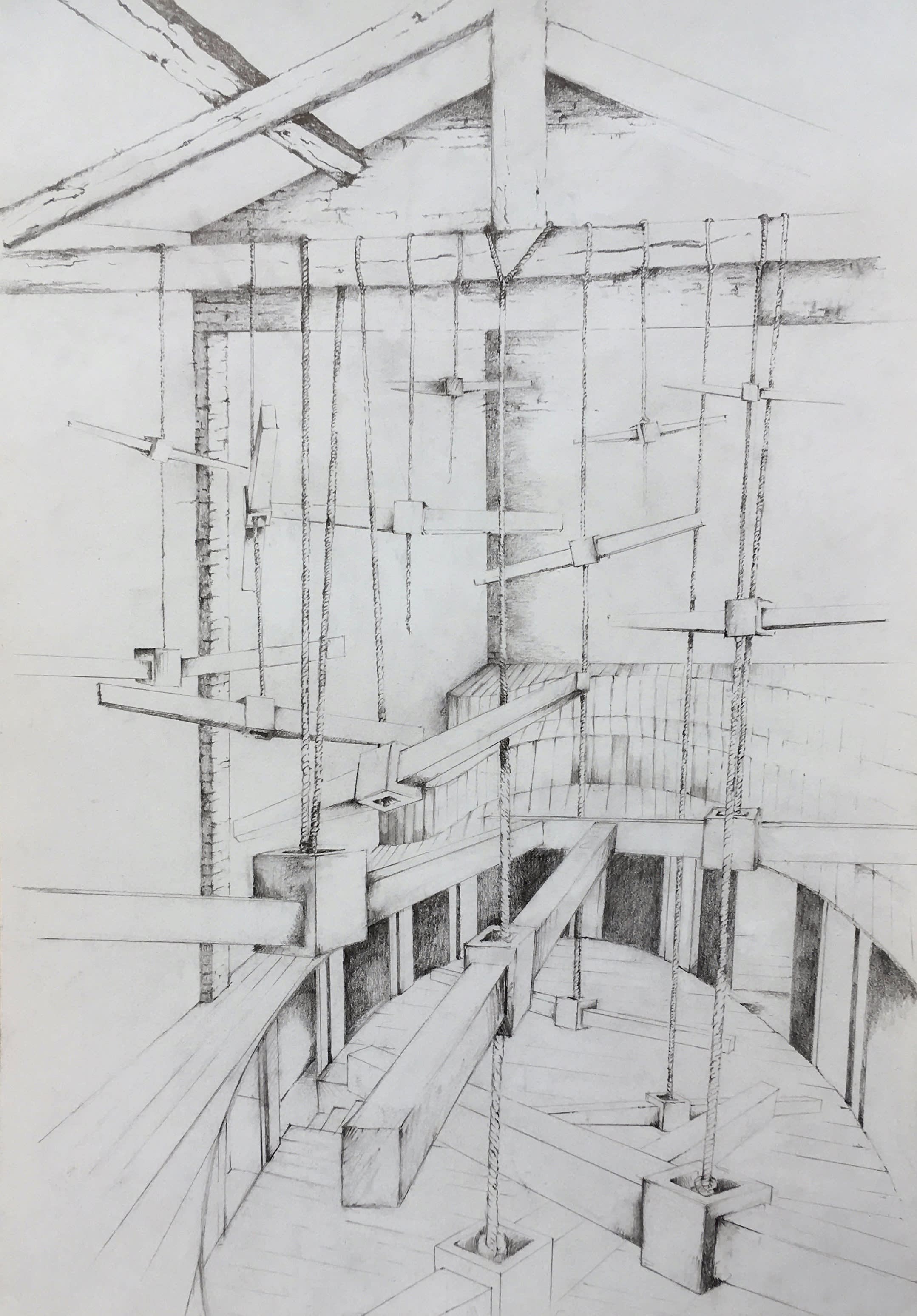

MF: I first saw the Ancore theatre on 20 June and from that point I started making more anchors, but I also needed to do a drawing to show the owner of the space what I planned to do. I decided to make a drawing that would not just be a sketch, as I might normally do, but to try and use an approach that placed more emphasis on the use of line and confer an accurate idea of the space and how the anchors would be placed. Realising that there was a Working Drawing section in the Drawing Prize (this is only the third year for this), I felt it was worth putting a greater effort into this drawing and, fortunately, it paid off. I made a second drawing at the time, but a few days too late for the submission. I would almost certainly make new drawings this way in the future.

Interpretation: Plough 6, 2020, drawing on paper, £900 unframed.

CS: So typically, what is the relationship between sculpture and drawing / printmaking - and between two-dimensional and three-dimensional space - in your work? How have you come to work with such spatially different mediums, and how does space play a part in these three ways of making art?

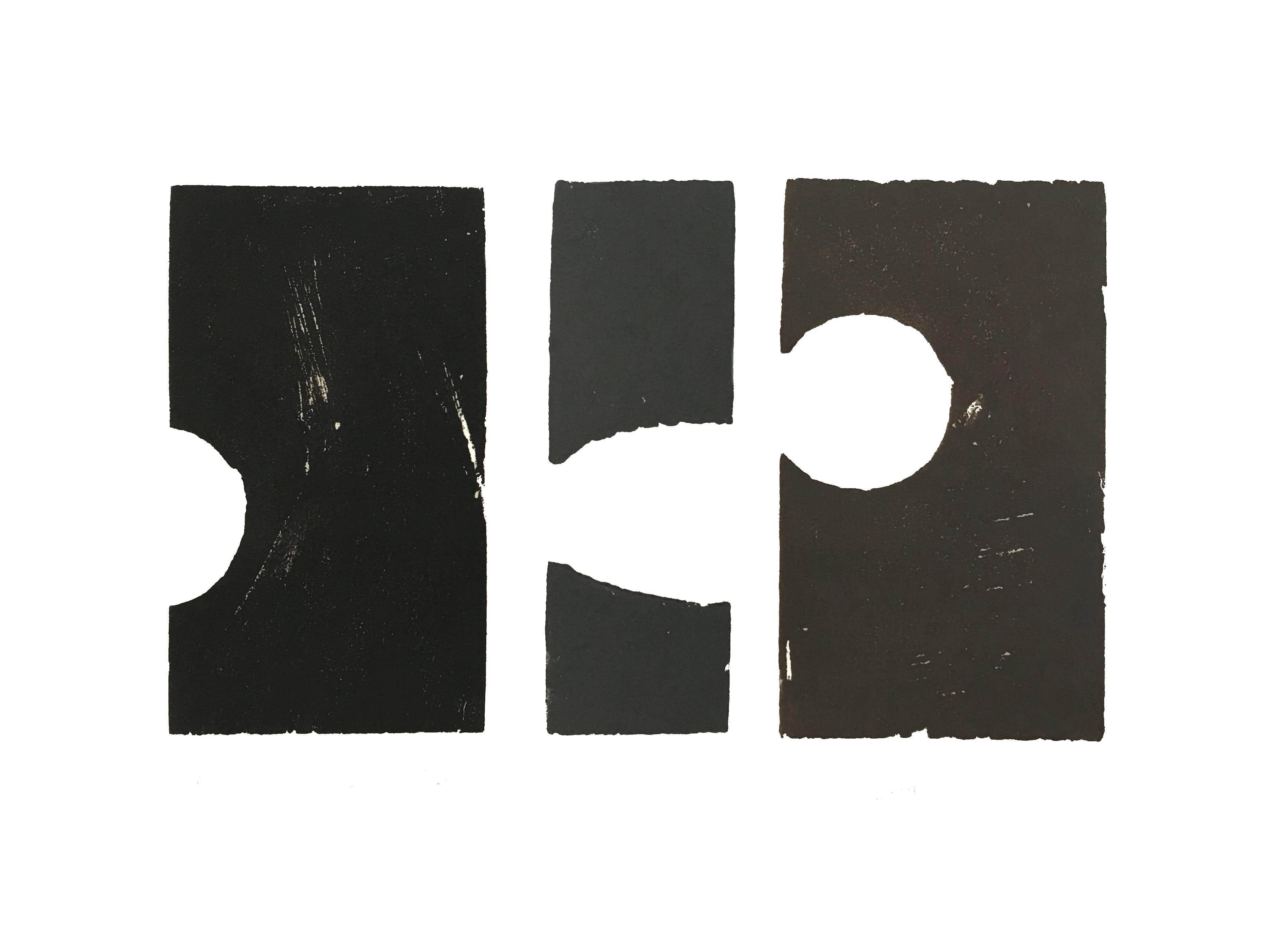

MF: Spatial relationships are at the core of what I do. Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd commented that "Space is made by an artist or architect; it is not found or packaged. It is made by thought" ("Some Aspects of Colour in General and Red and Black in Particular", 1993). Further he has said, "works of art, and in particular sculpture, create space and define the dynamic nature of space" ("Specific Objects", 1965). With sculpture, the third dimension exists as a reality. With works in a two-dimensional plane, one has to consider space in a different way. For instance, in some drawings I would rely upon the use of conventional perspective to create a sense of space so that I can get an idea of how a sculpture might look or how it could be visualised in a given space. This is what I did for the preparatory drawings for the Ancore installation. But with many other drawings I do not try to create this illusion of space in the same way; I can create depth within a drawn two-dimensional shape by applying different weight to the drawn line - ranging from a heavy line to a fine, more delicate line. Depth can be made even on a flat shape by using tone / shading. This is apparent in the drawing interpretations for the Plough and Tenement sketches. I also create space by placing one shape in relation to another, thus bringing into play ideas of negative and positive space, the space between objects, and the space around them. This is very much like with an actual sculpture. This has been the main consideration with my recent Pezzetti prints. A lot of thought is given to the exact placement of each printed shape to get its size and position right.

Pezzetti 10, 2019, woodblock print, £200 unframed.

CS: Do you think that working in this new way - installation - has had an influence on how you see spatial relationships between wood or stone structures and their environments? Could you describe the space in Ancore for those of us who can't visit it in person?

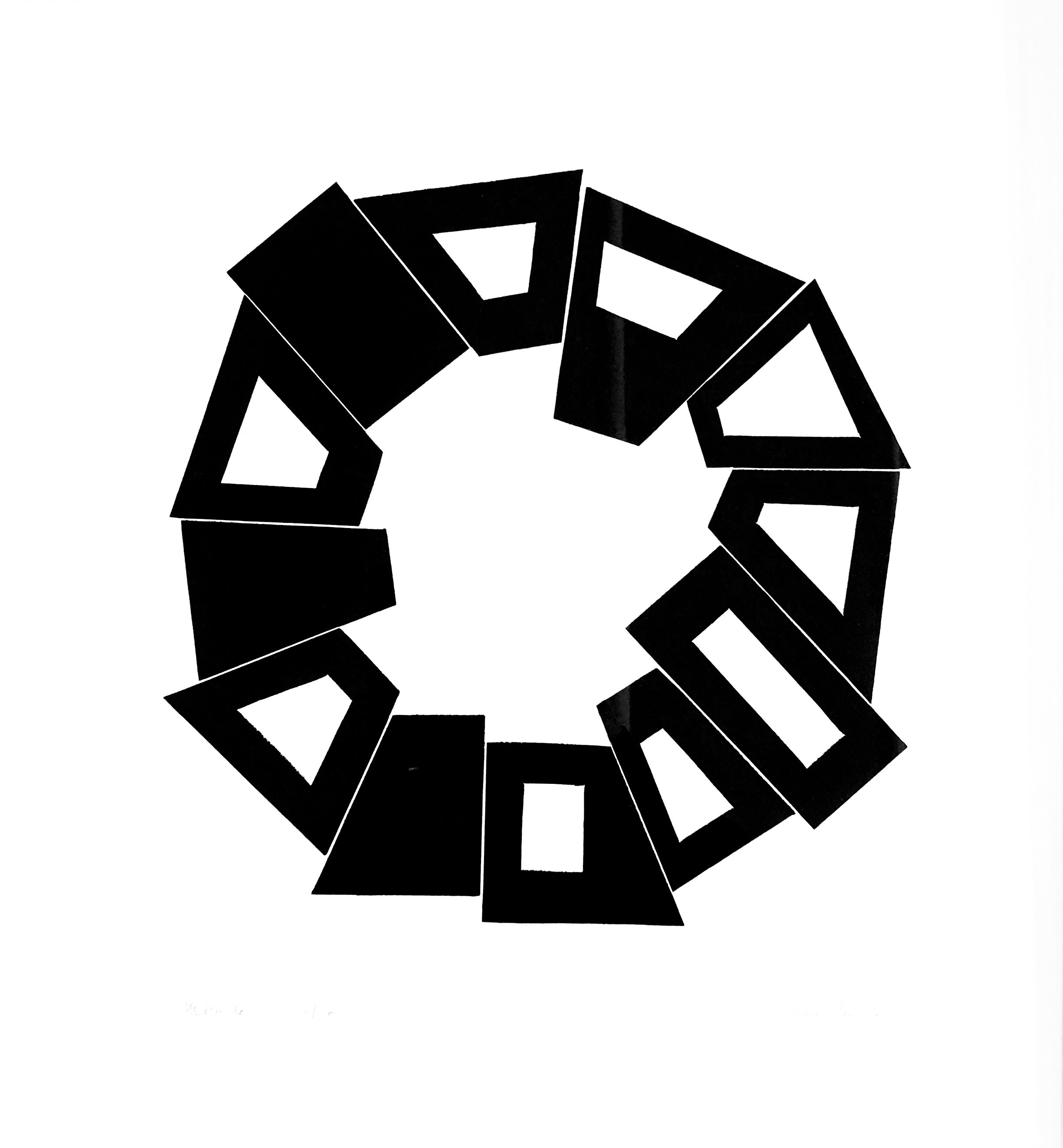

MF: The installation allowed me to put together multiple objects, albeit of a similar shape, and to work in relation to a given space that was not a gallery. When I was shown that small theatre I was immediately struck by how important it would be to use that space and I had to consider very carefully how each anchor needed to be placed, due to the various viewpoints of the audience, and also how the filming of the project would take place (the only truly public viewing of the installation was going to be on film). We began the installation by hanging anchors from the main transverse beam - this is shown on my drawing for Trinity Buoy (below). I was very insistent on the individual placement, what could be seen from where, how it would be seen. The ropes and the anchors themselves act to not only fill space, but to divide and delineate the space. They displace it and create both negative and positive space interactions: this is crucial. Ancore was a fully immersive installation. If I made this work in another building / place, it would be different.

Malcolm Franklin's drawing in the Trinity Buoy Wharf Drawing Prize (virtual) exhibition, a design for his Ancore installation project.

CS: Would you do another installation project in the future? Do you have any other ideas that have been percolating for a few years - as your Ancore work had been since 2008?

MF: I have plans for another installation, which I have already started work on. The idea came to me a little while ago and is beginning to come to fruition, but it needs refinement. Without giving too much away at this present moment, it will involve the use of 'found objects' and carved stone pieces and will also hang, like Ancore. Again, finding the right sort of space for this is important. There is a way to go on this but it could happen this year, or next. Then I also have another concept for an installation, which is definitely at the early 'percolation' stage.

Offset Curve, 2014, sculpture in Prun di Verona, £3,600.

CS: For you, what's the relationship between drawing and some of your other works?

MF: The process of drawing allows me to consider many things before committing to a sculpture. That said, I have used the drawing process in what one could consider mixed media works like my Moche canvas pieces, Shifting Embrace collages, and Taglio works on paper, all of which use dust. These explore the spatial relationships between the 'ground' areas of dust and the dark grey / black lines. The placement of those lines is fundamental to the composition: they pull the work together.

Taglio 6, 2017, lithograph with ironstone dust, £350 unframed.

CS: You speak to this in your video about Ancore, but could you explain why the anchor form took hold of you? Where did this inspiration come from?

MF: In the video I mention that I first saw some Roman Anchor Stocks - this is what they actually are - in the Archaeological Museum in Palermo, in 2008, which I photographed. In a sense the anchor shape took hold because it had strong sculptural possibilities. Taken out of its normal context, that being an anchor resting on the seabed, and displayed on a concrete block in the museum, you can just focus on its shape and form. At least, that's what I do in these situations; I'm always doing that in museums and collections. That's how I see things in the world, I look at them for their potential to make art. These concerns are my 'inspiration'. Much of my inspiration for my shapes and structures comes from objects / things / tools / buildings / architecture, etc. Until starting art school I had made a lot of landscape paintings, then I had a turning point during my Foundation year and I really took up sculpture. It was at this point that I started to think about the idea of objects. I tend to look at old tools, maybe because they're hand crafted (this could be a much longer discussion). I grew up in a farming family and there were tools and machinery everywhere. As I child I was never fascinated by how they might be put together or how they work, like an engineer, say, I just registered all these things as interesting shapes.

Hesper 6, 2014, linocut, £500 unframed.

CS: What's next?

MF: What's next - I have probably touched on this by saying that I am in the process of working on a new installation. Other than that, I bought a large supply of alabaster recently and this is likely to keep me going for most of the coming year. I also plan more Plough type sculptures, which could become a series of five or six. More ideas than time, unfortunately. Eventually, with a bit of assistance, they will get done.

Model 2 for Heron Tenement, 2016, sculpture in bronze on a granite base, £3,500.

Comments

Fantastic works and love the ideas. The path between drawing, sculpture and engineering is so appealing. It looks like a wonderful space to be in and around.

The only frustration is that I cannot see it in person.

Thank you.